Before I continue my travelogue, I want to share some information about the unique ethnic groups in this part of the world and some of their tragic history in the recent past. My interest spawned from my years in Namibia, where I met friends from the many different African tribes that make that country so fascinating and strong. It was intensified a few years ago when I met a young man – one of my teacher trainers – who told me he was Hmong and that his family was part of the “large diasporic community in the United States of more than 300,000” (Wikipedia) that escaped to the US and other countries after the “Secret War.” I had no idea what he was talking about, and what I have since learned has blown my mind. A part of my country’s history during my lifetime that I might not otherwise have learned about…

Note: This post is different than the other posts on my blog. More than a walk along trails while viewing landscapes, it will feel like a walk through museums while viewing exhibits, displays, and information panels. I find the first part of this post interesting and the last part heartbreaking. I hope you find it valuable.

I had some familiarity with the Vietnamese community in the United States that grew after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Many of them live and work in my hometown of San Jose, California, the US city with the largest population of Vietnamese Americans). And I also knew a bit about the large population of refugees from Laos living in Thailand. But the story of the Hmong people during a “Secret War” in Laos was completely new to me and led to a deep dive of research and study.

In addition to links to Wikipedia and other online resources, I am attaching photos I took of exhibits and slideshows in ethnology museums and other museums focused on the Indochina wars, so full credit and copyright to them! They are staffed with tribe members and have fascinating exhibits but are seriously underfunded and falling behind in the portrayal of current conditions. Should you ever find yourself in these towns, please pay them a visit. You might be brought to tears, but you will not be disappointed!

Highland People Discovery Museum, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Hilltribe Museum, Chiang Rai, Thailand

Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre, Luang Prabang, Laos

UXO Lao Visitor Center, Luang Prabang, Laos

MAG UXO Visitor Information Centre, Vientiane, Laos

War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

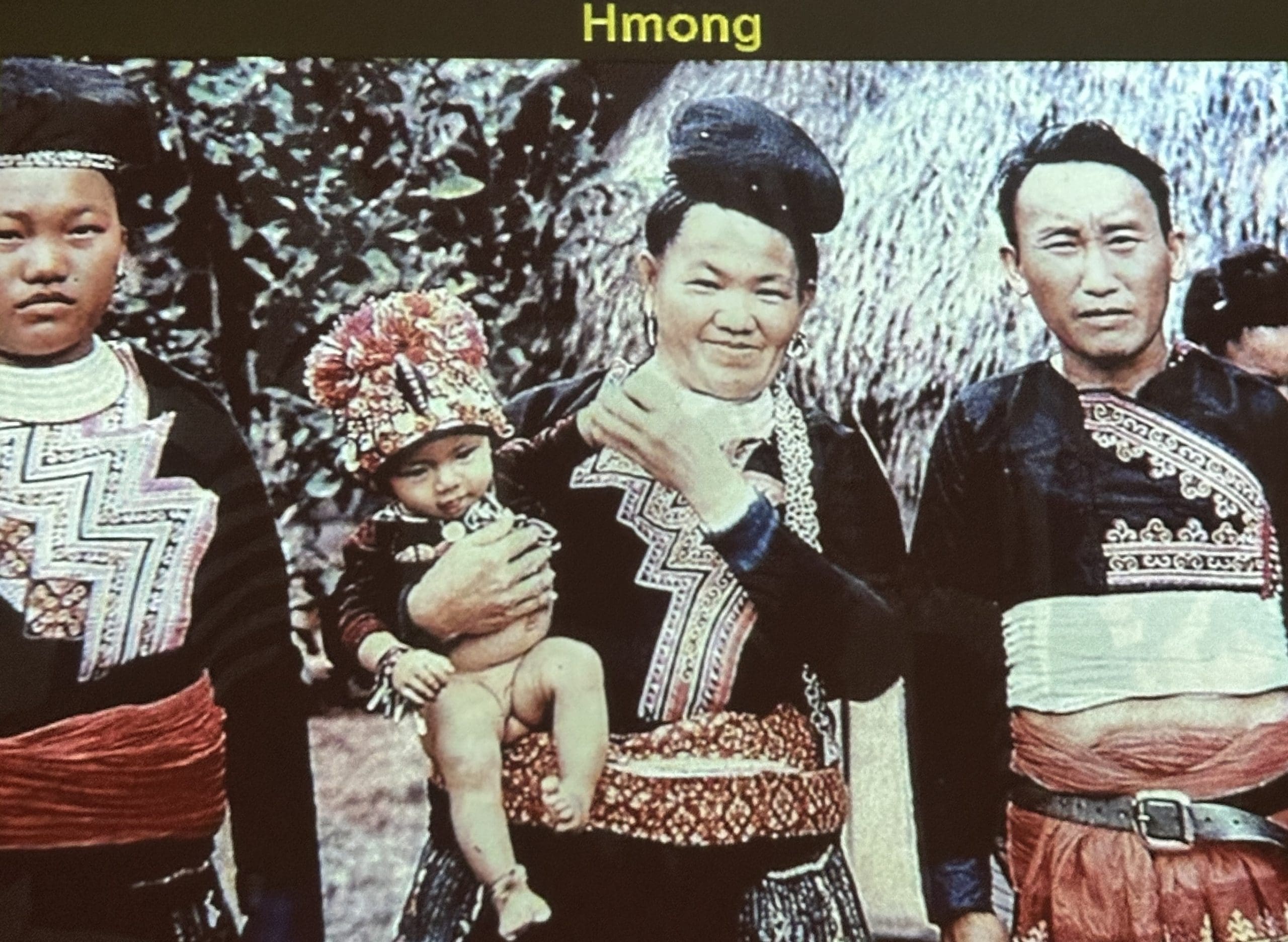

The Hmong are only one of many minority ethnic groups in Southeast Asia that have migrated from as far as India and China. Loving both mountains and hiking, my interest is particularly in the hill tribes, and I visited villages of five of these tribes during my trekking holiday to Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam.

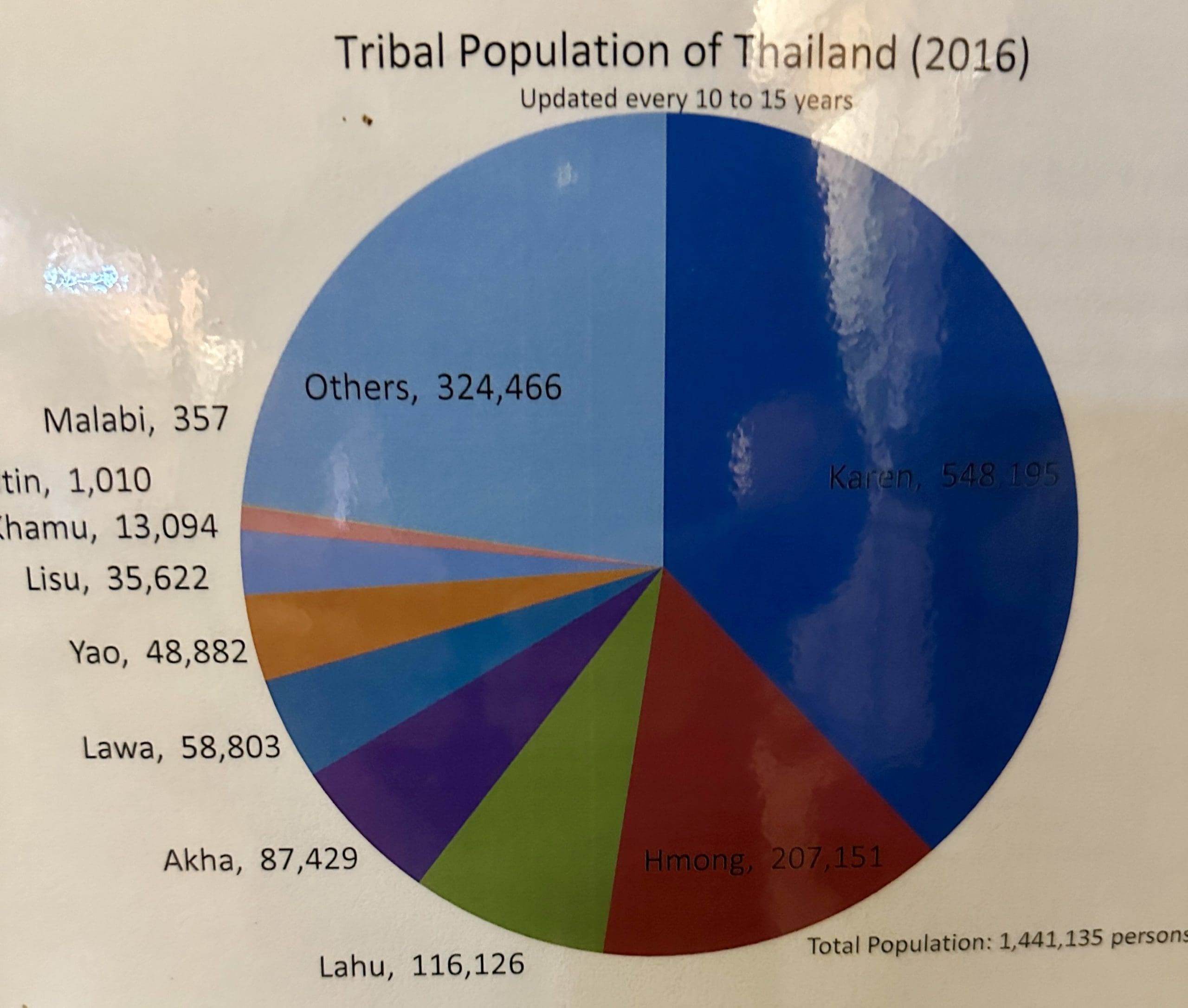

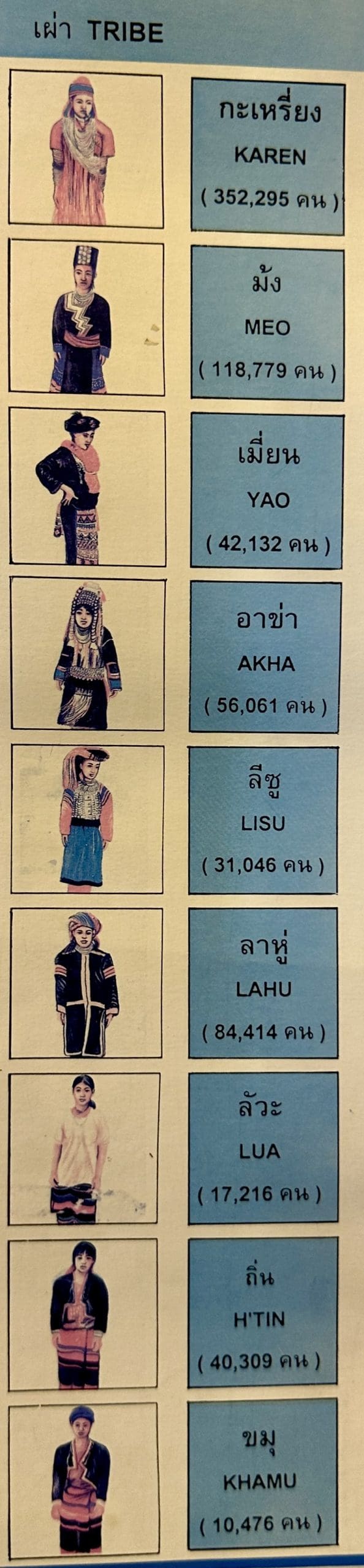

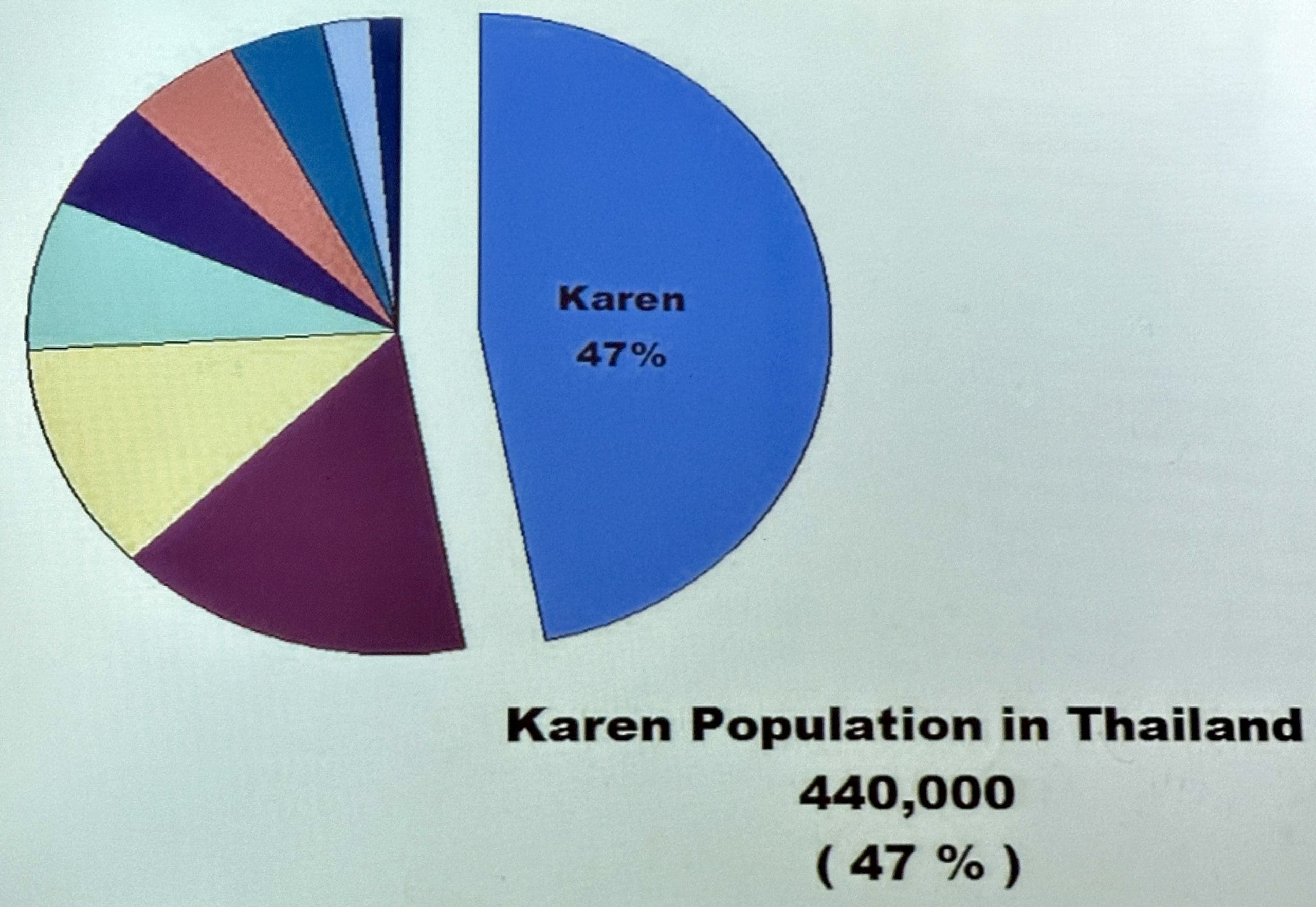

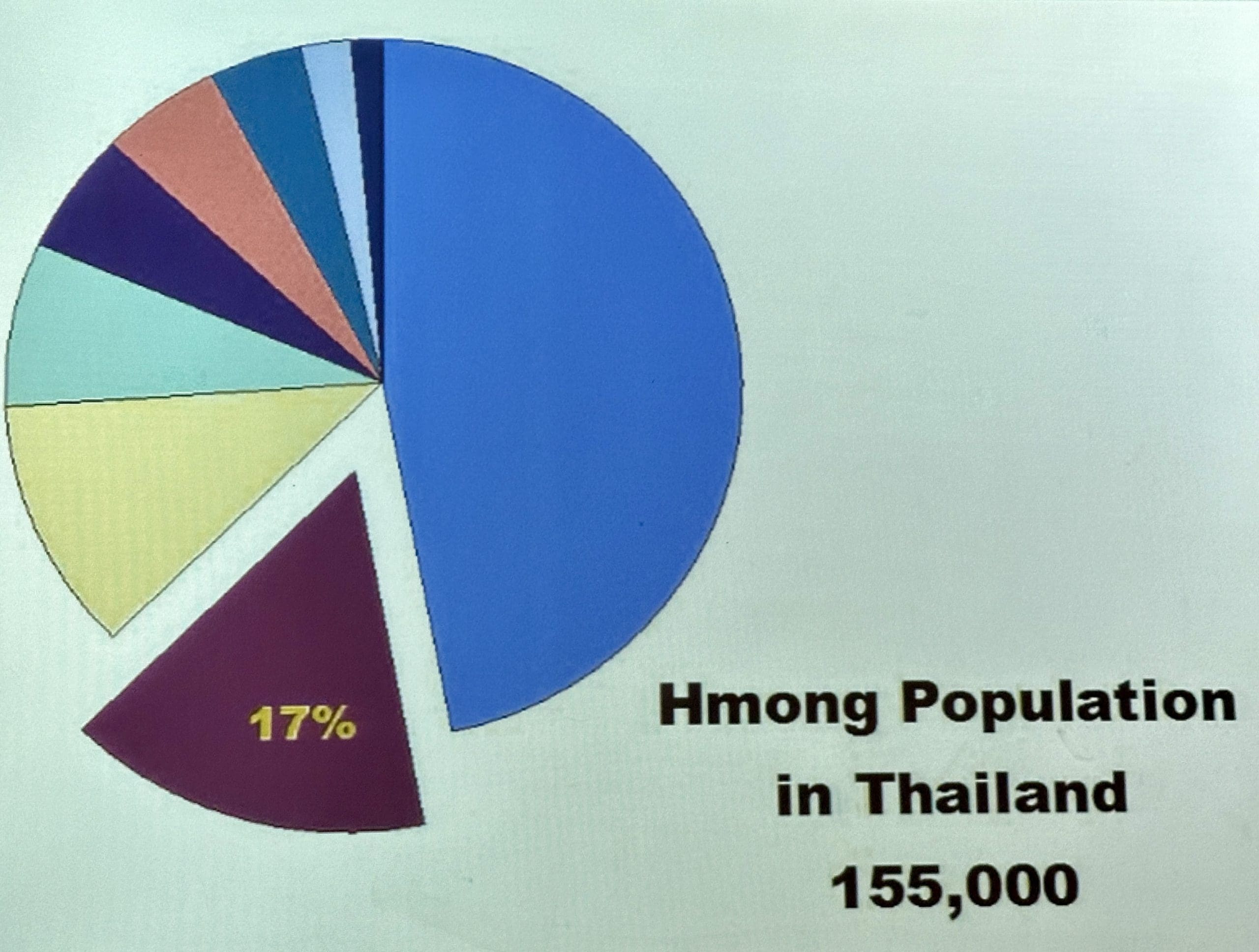

In Thailand, the national government recognizes 11 minority ethnic hill tribes in the country despite not granting some of their members the benefits of full citizenship. Many of them are considered refugees from neighboring countries, like the Hmong from Laos. This includes even those people who have been born and raised in Thailand. Despite knowing no other home, living there for their entire lives, sometimes working and paying taxes, these people cannot vote or receive many of the social services available to citizens.

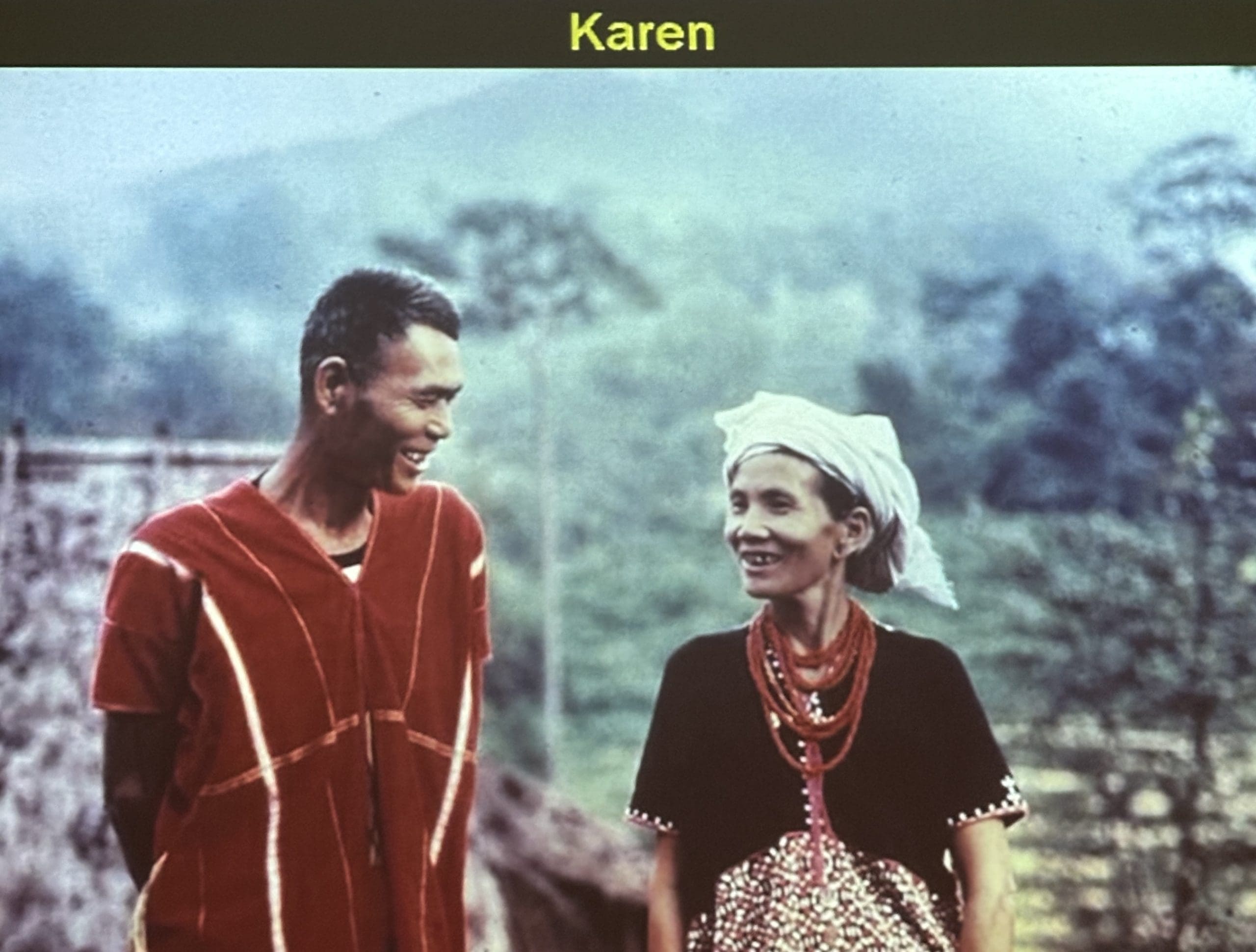

My first trek, to the Mae Wang Area near Chiang Mai, was led by Montree, a Karen guide, and included stays in a few Karen villages and homes.

The iconic Padaung people, famous for their long necks, are a sub-group of the Karen Red tribe. They are found mostly in Myanmar but with a few villages near northern Thailand cities that are popular with visiting tourists.

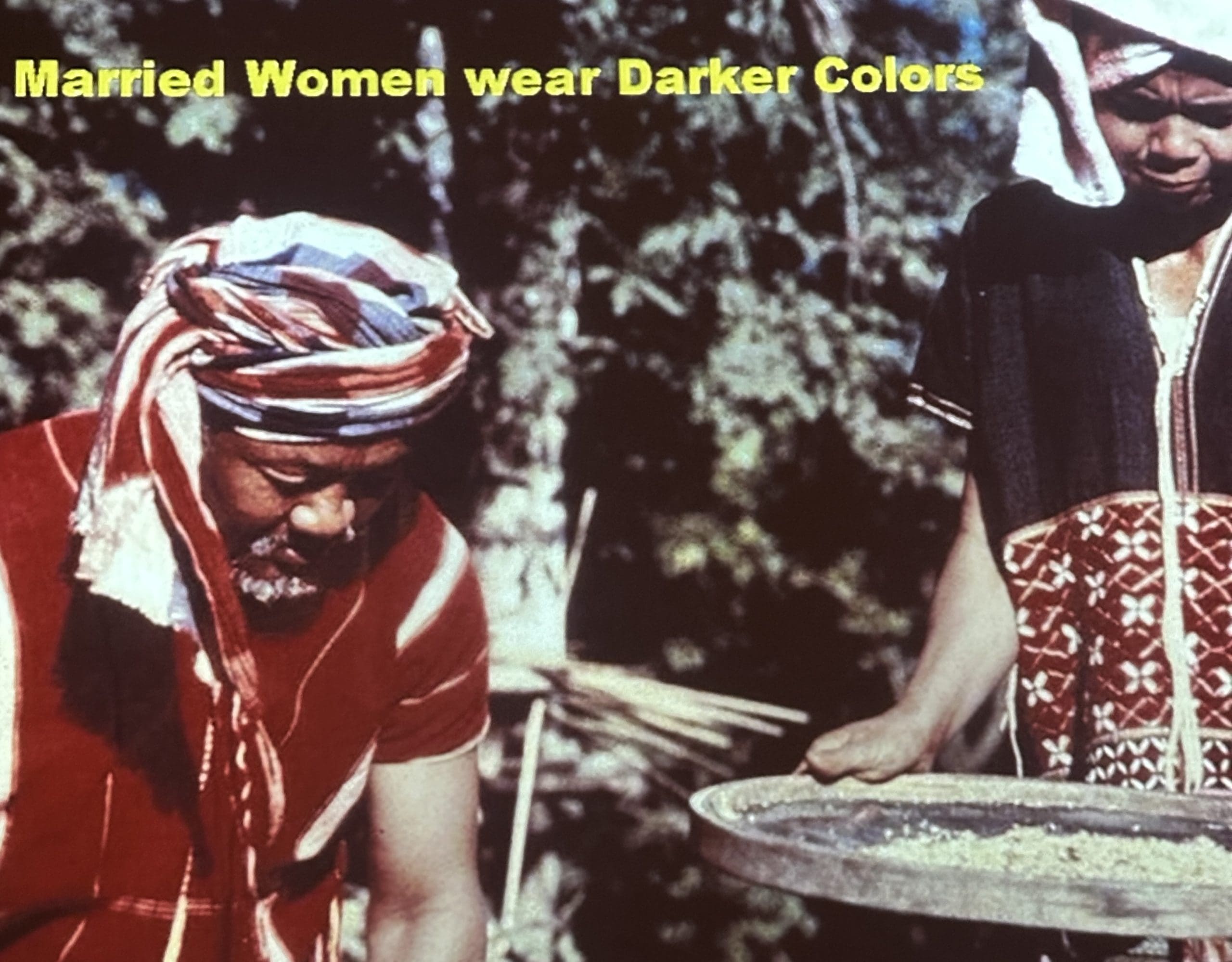

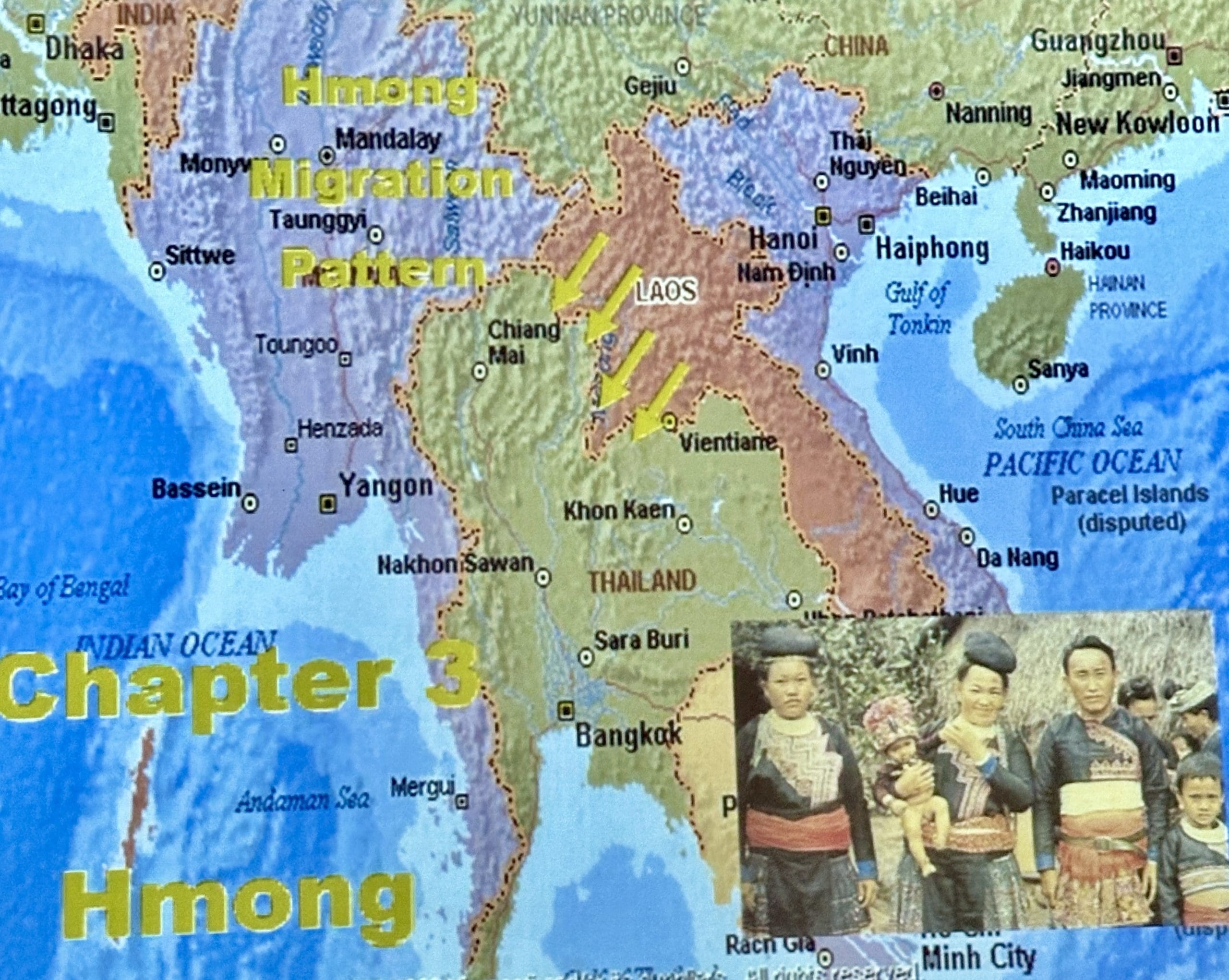

The Hmong people are the epitome of a hill tribe, much more comfortable at higher elevations than in the valleys and along the rivers. In a future post, I will describe another multiday trek I made in Laos when I stayed in a Hmong village at the summit of “Big Mountain.” Their ancestors migrated originally from China to northern Laos in the 17th and 18th Centuries and escaped or were driven into Thailand after the 1975 end of the “Secret War” in Laos.

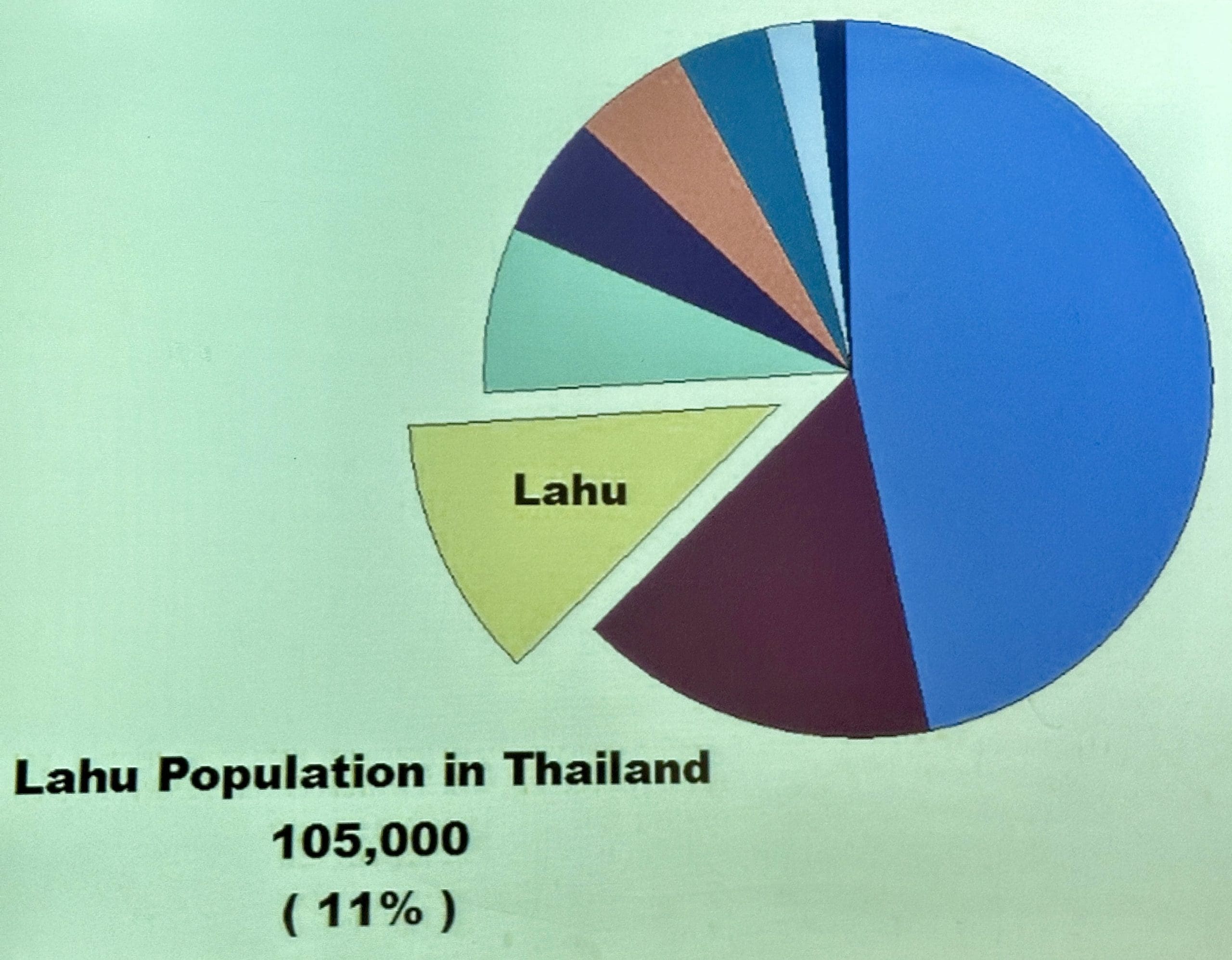

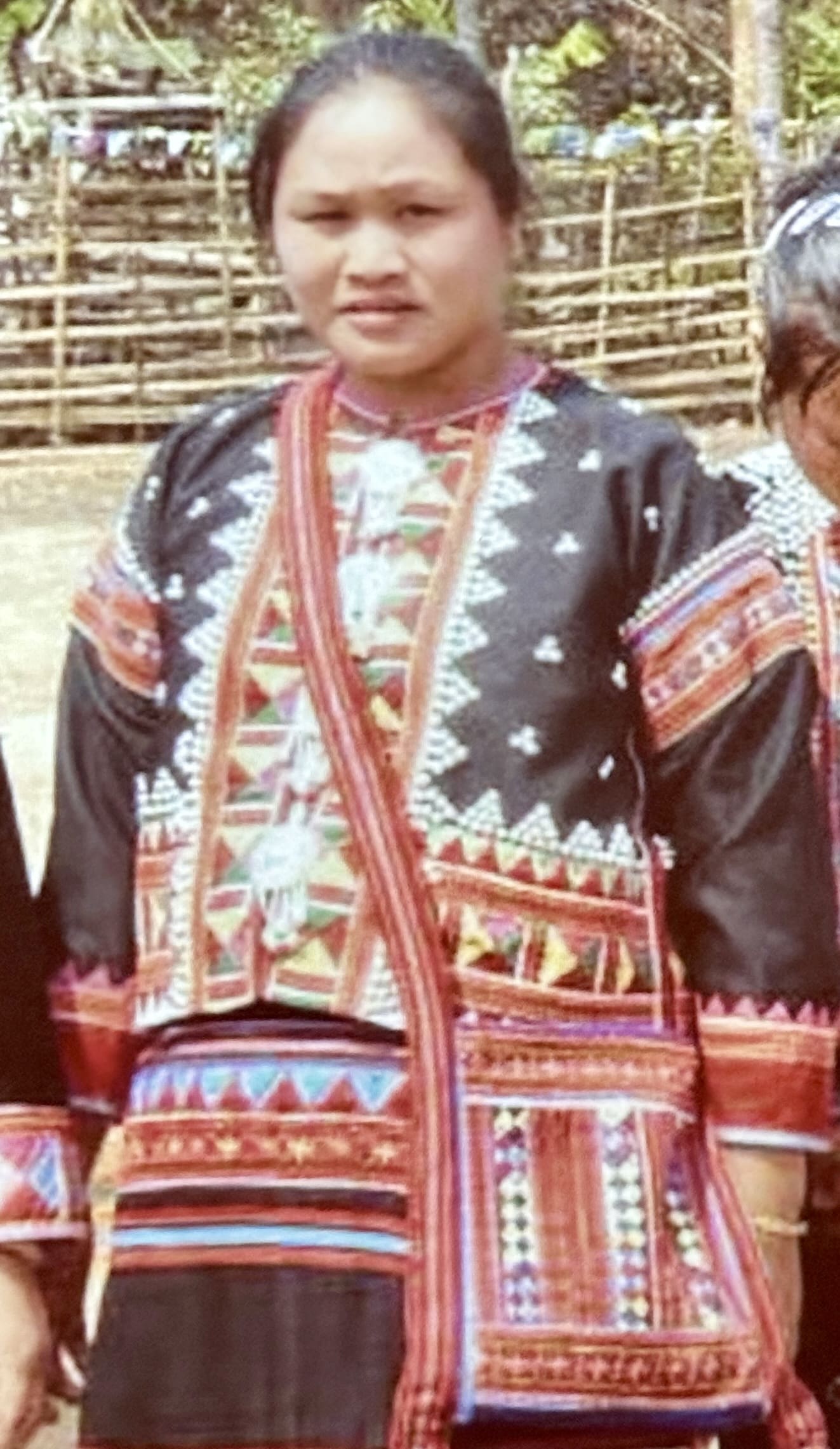

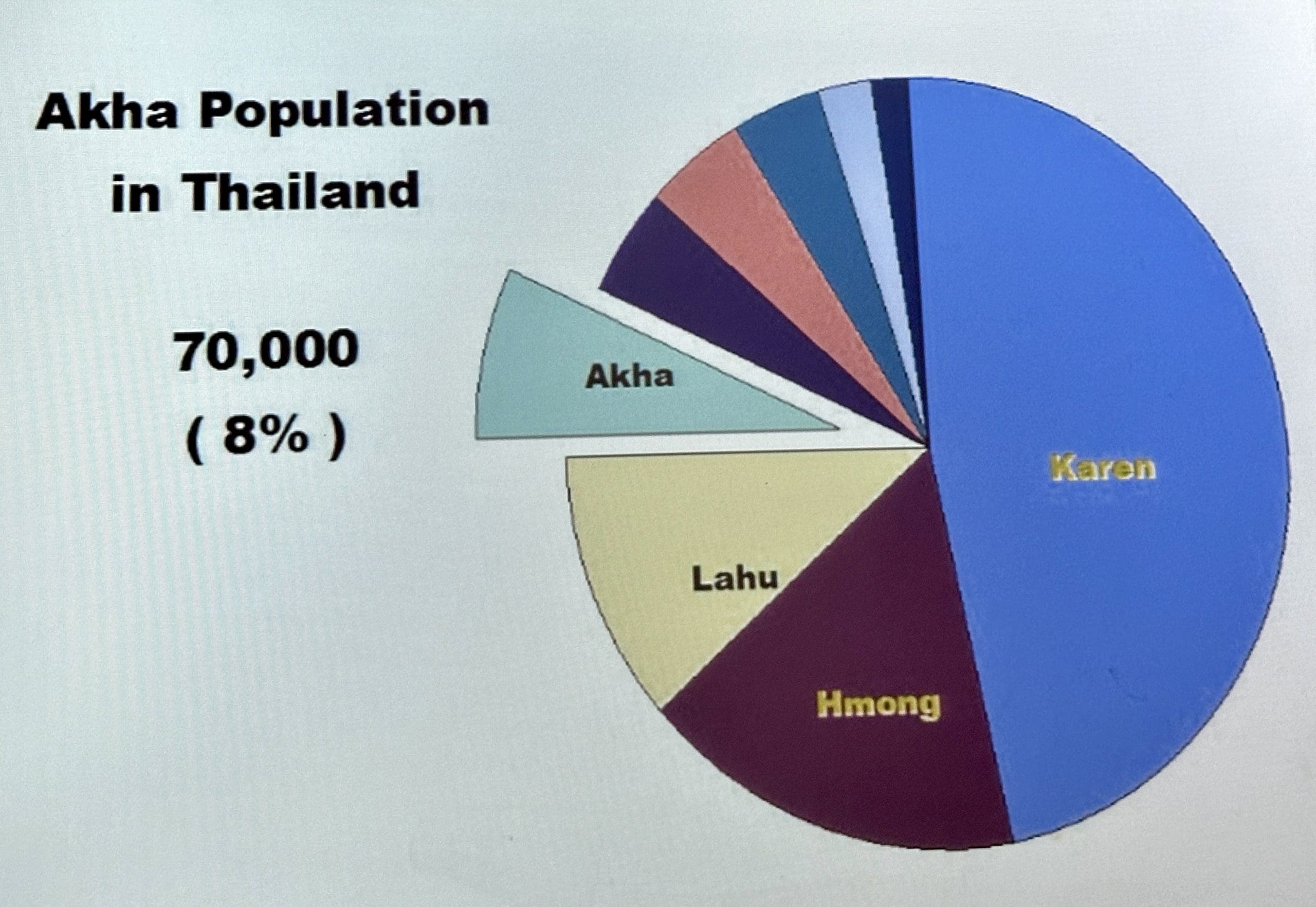

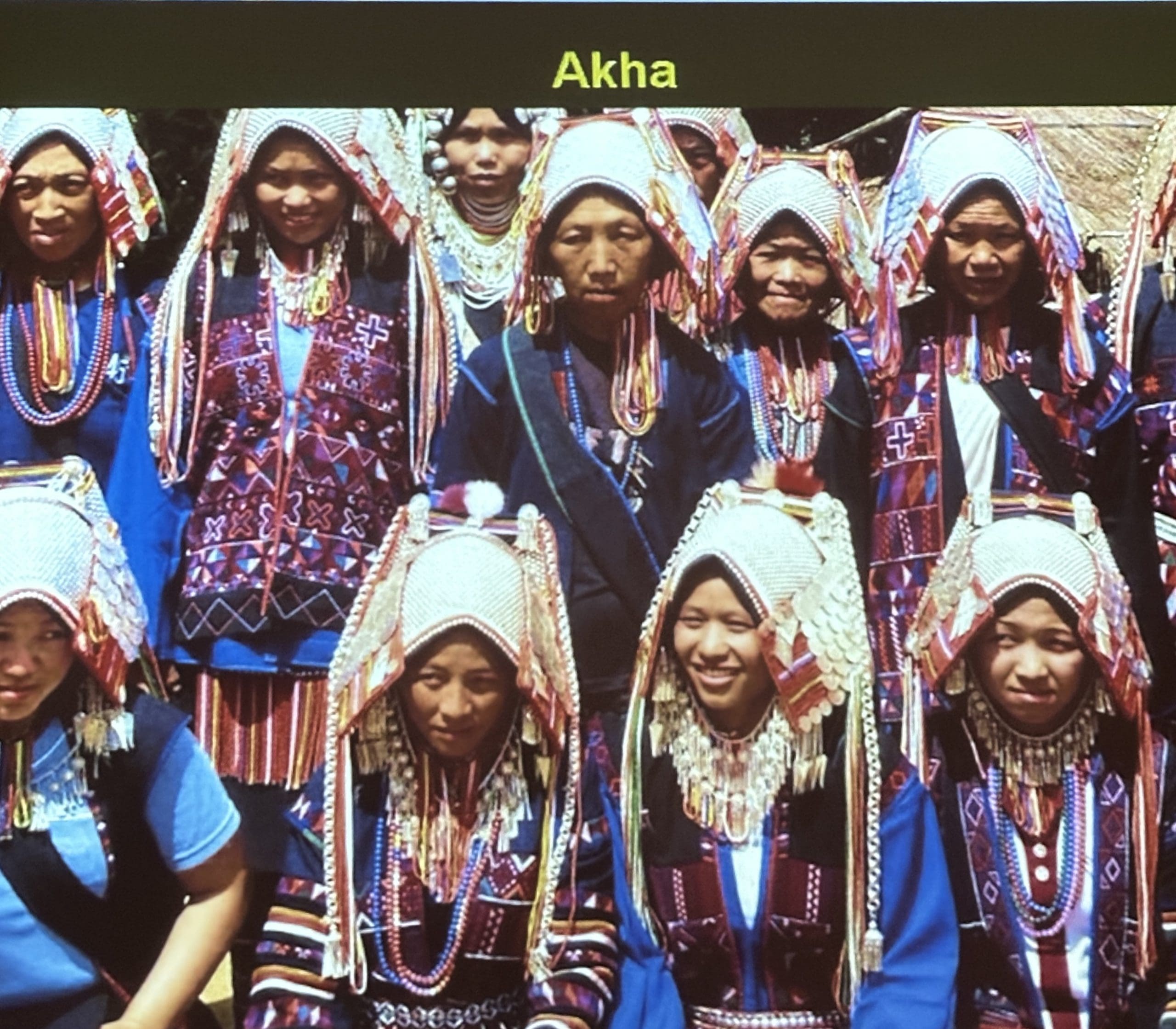

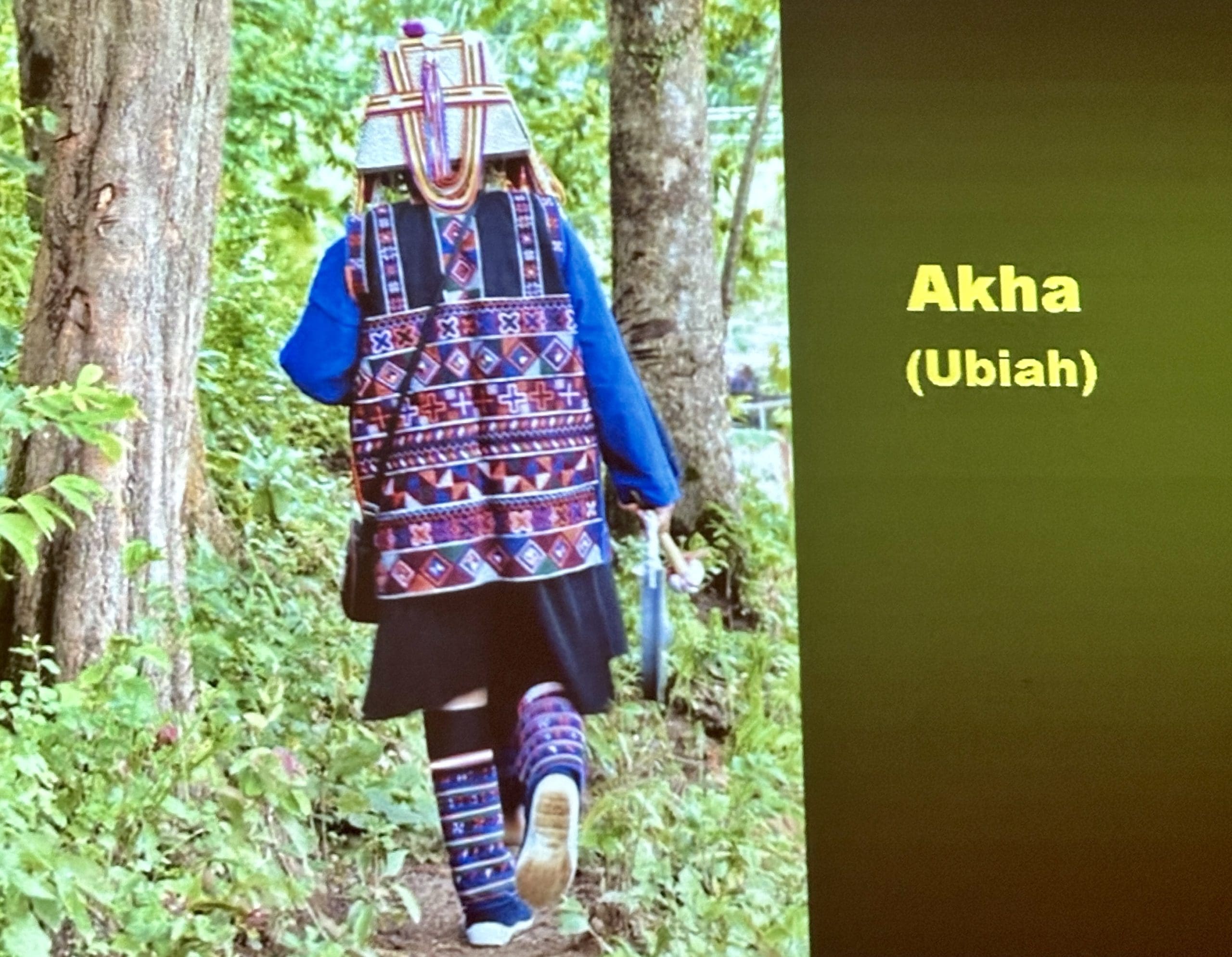

In my next post, I will describe a multiday trek I made out of Chiang Rai, Thailand, to visit mountain villages of two tribes that have become increasingly intertwined on the high slopes. The Lahu and the Akha have even begun to share words between their languages. Both are considered hill tribes, but they live and grow their crops below the high peaks popular amongst the Hmong. I had a Lahu guide for my trek, and we stayed the first night at his home in a Lahu village.

On the second night of my trek out of Chiang Rai, we stayed with friends of my guide in an Akha village.

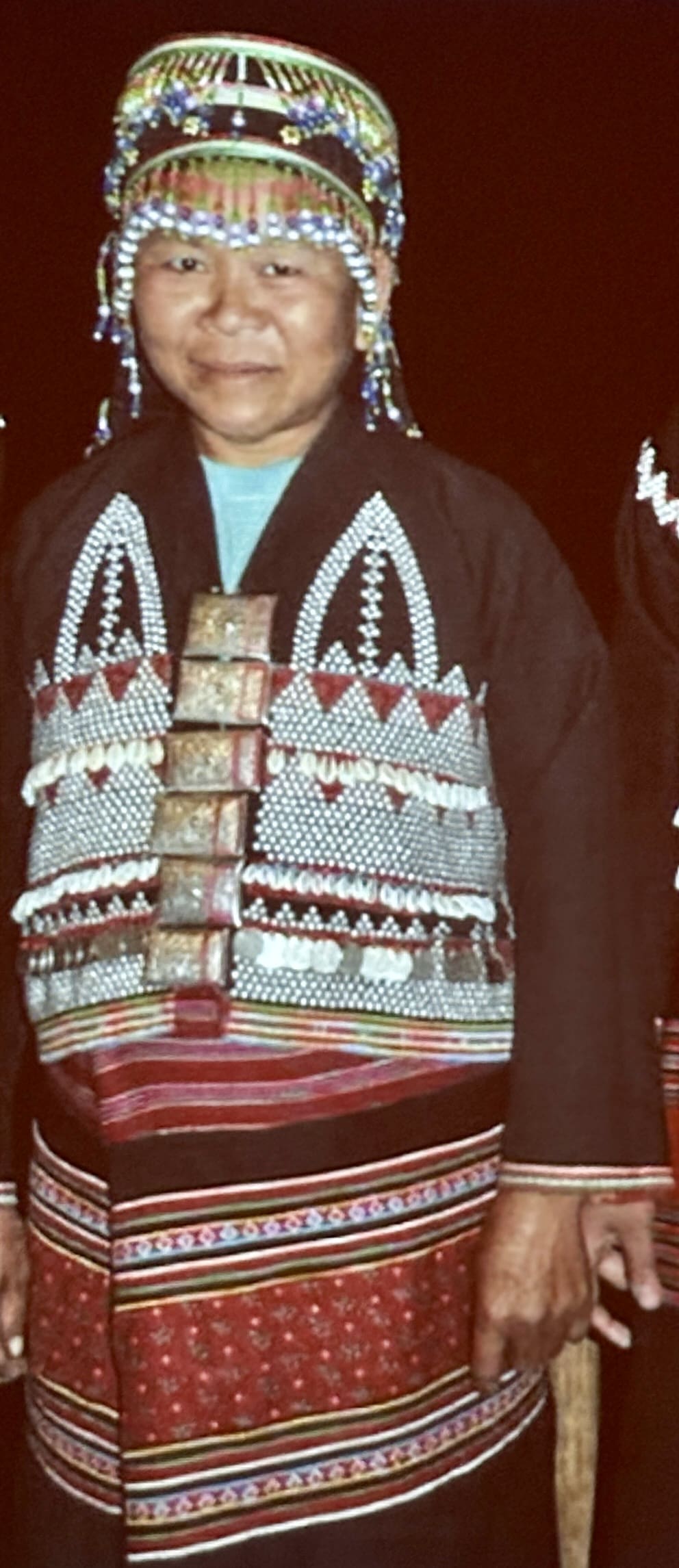

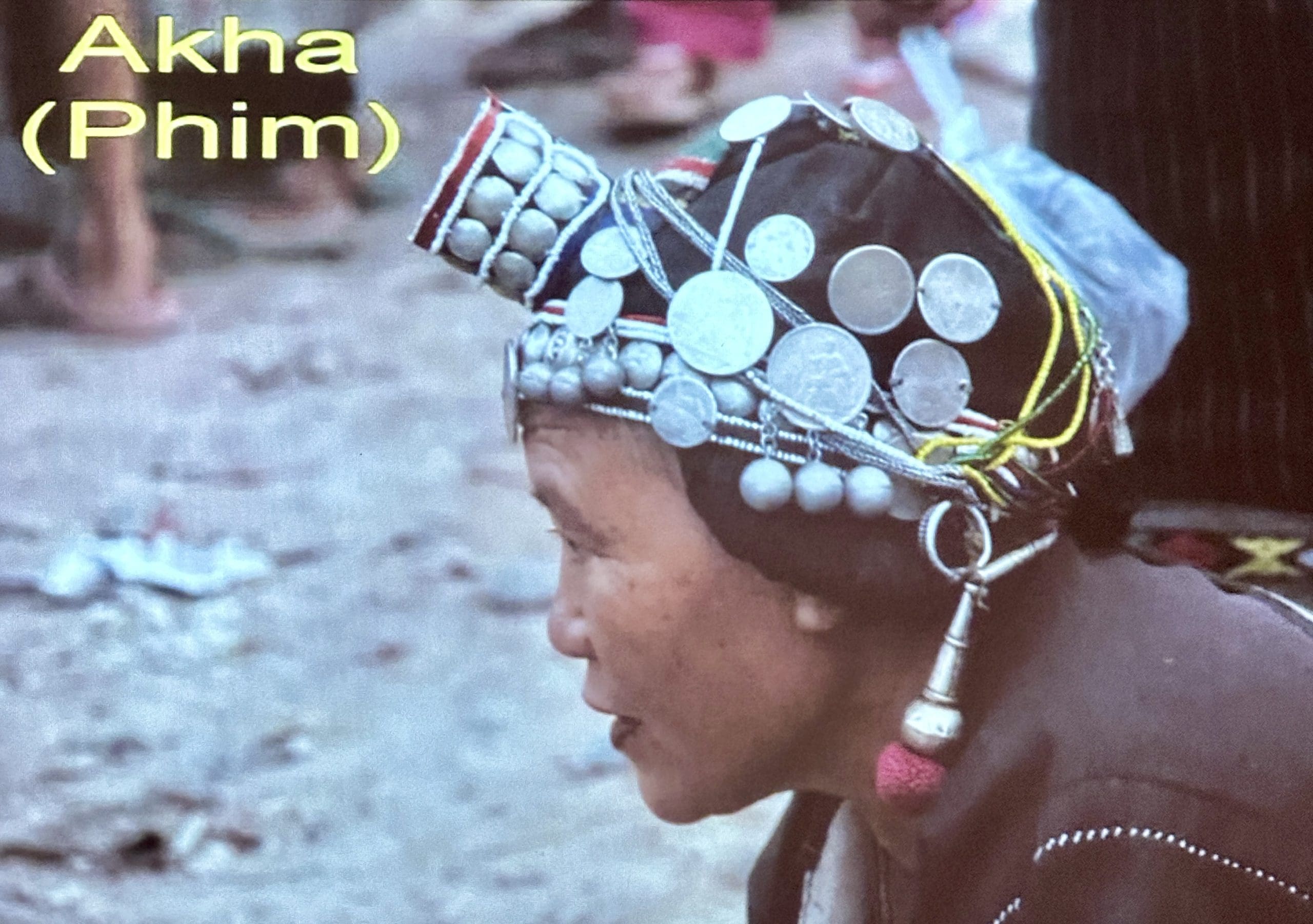

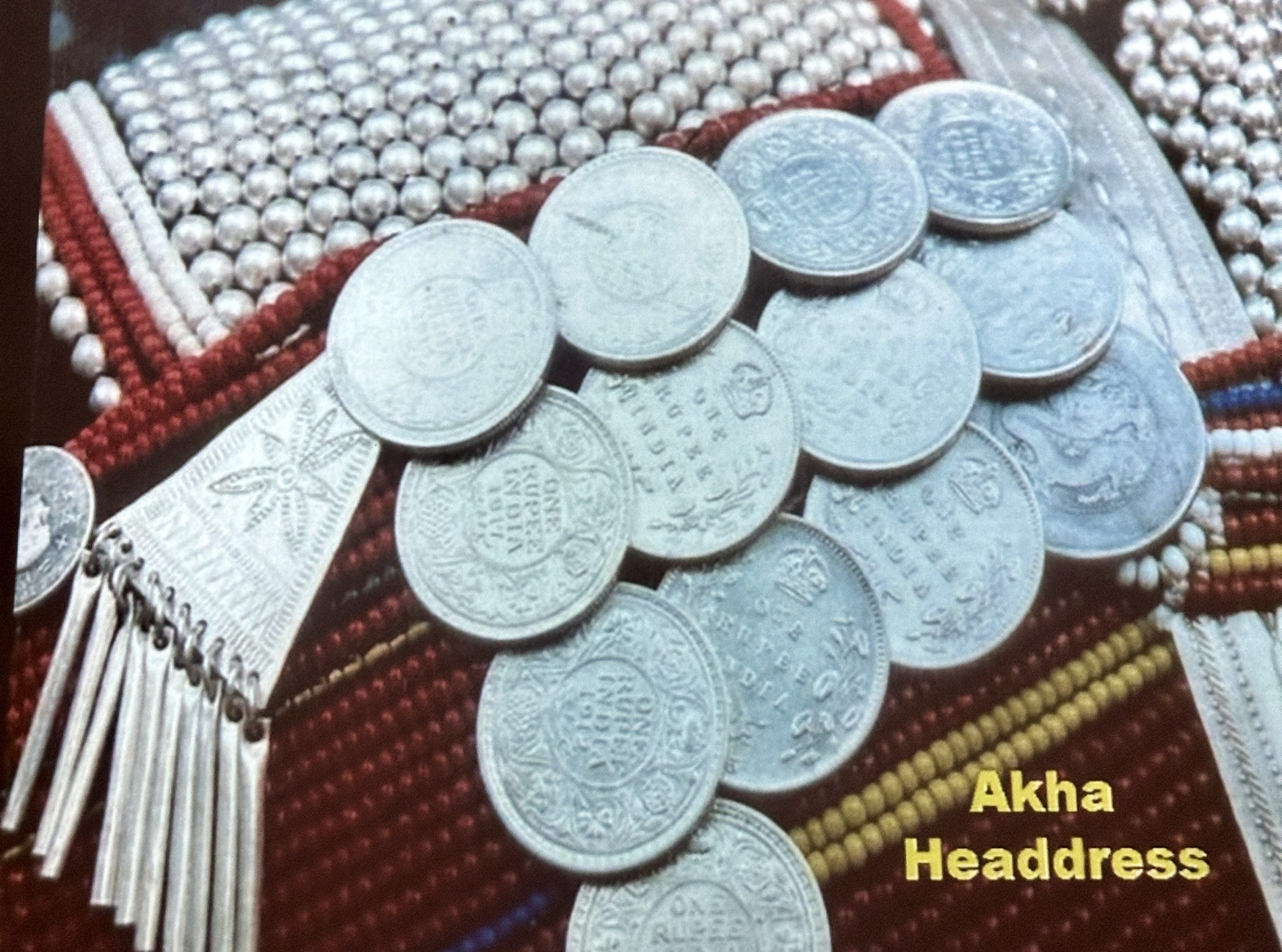

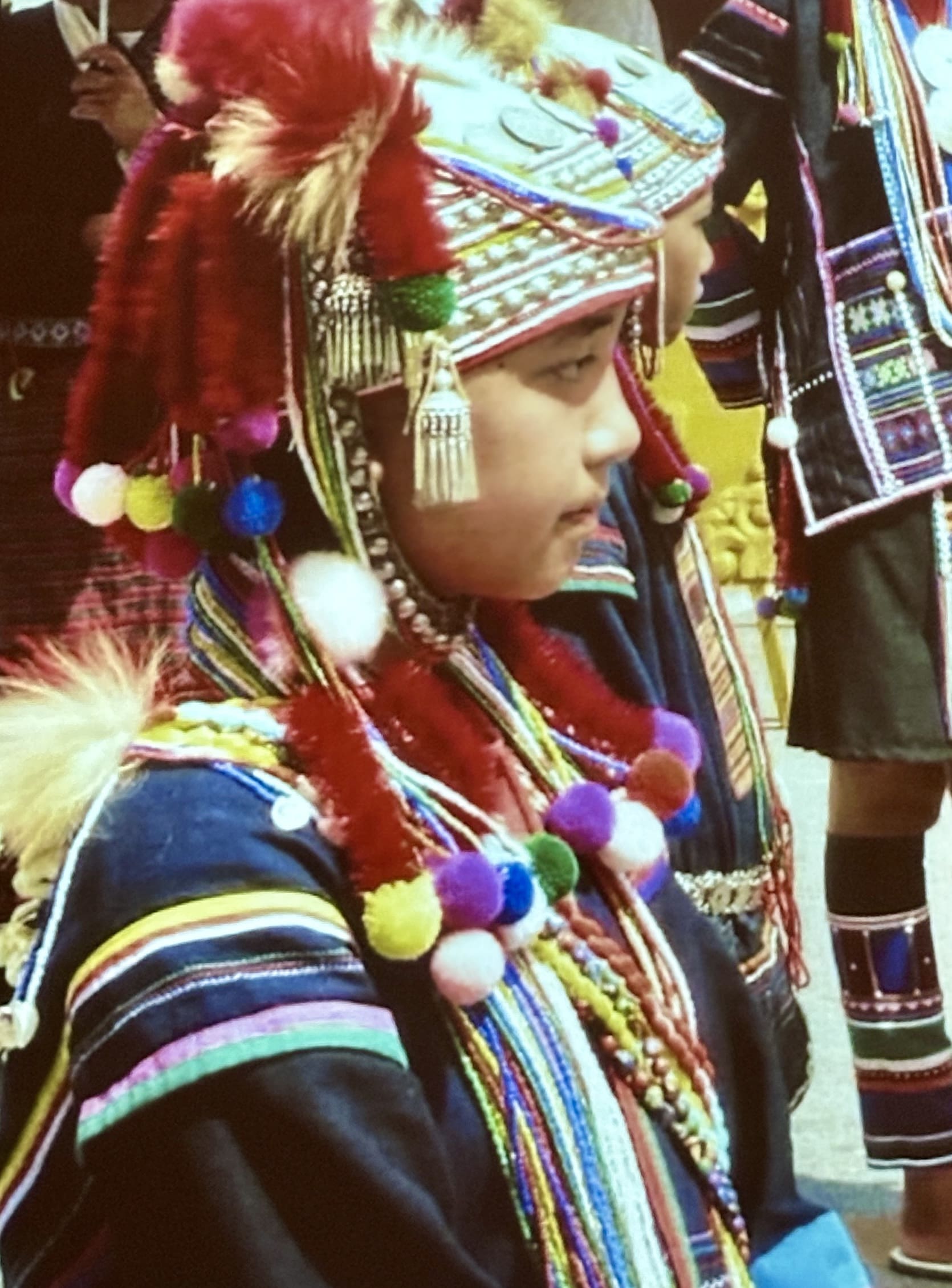

I saw firsthand the elaborate coin-enamored headdresses the women wear. I was told most Akha women only wear them for special occasions but that some of the older women wear them all the time. I watched one Akha woman getting into the bed of a pickup truck to join other women going out to work in the fields for the day. She was wearing her heavy-looking headdress! When I mentioned to my guide that it must be very tiring for her to carry so much weight, he replied: “They’re used to it.” I cringed for a second at what I thought was a callous statement, and then I thought: “Yeah, he’s probably right!”

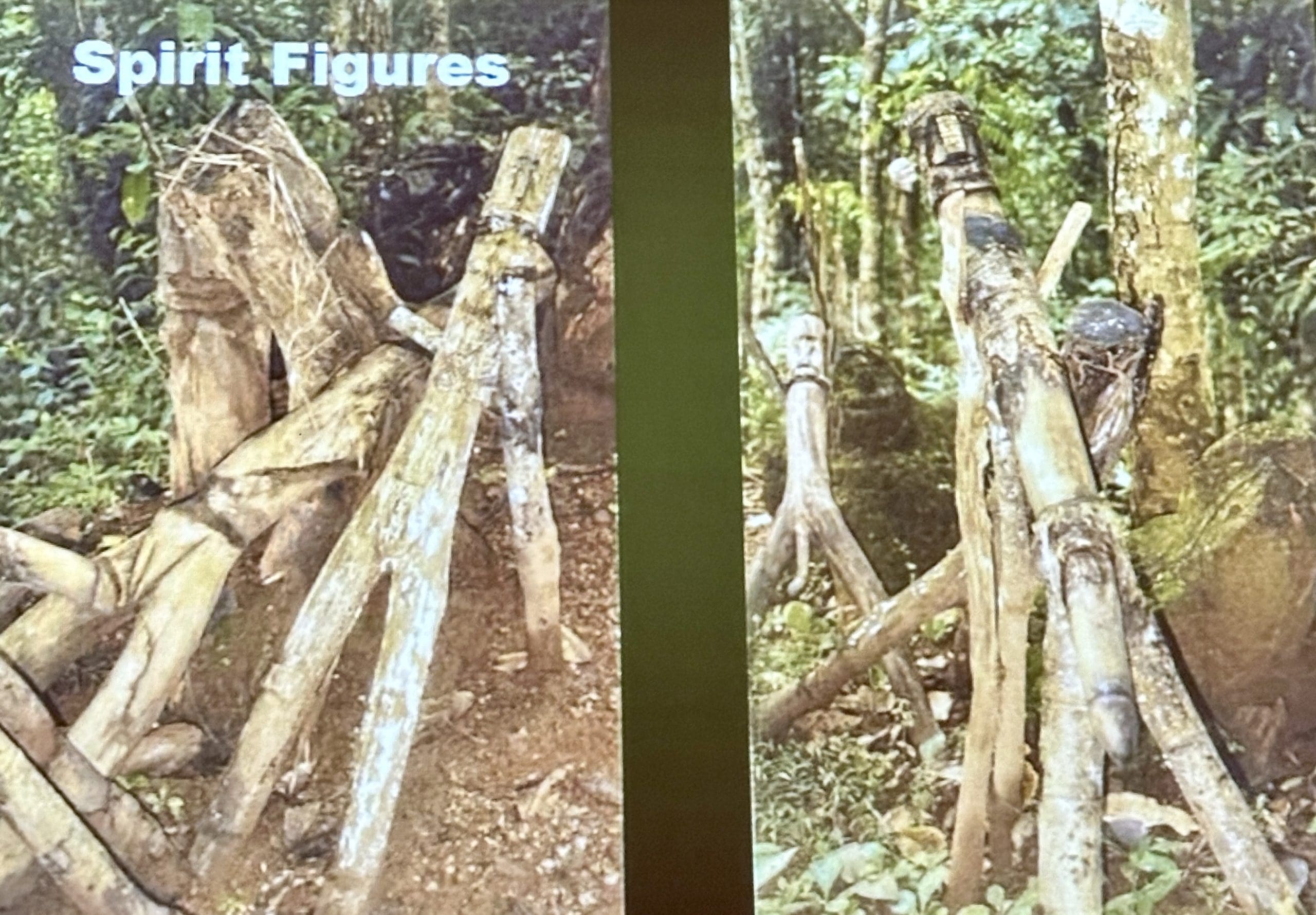

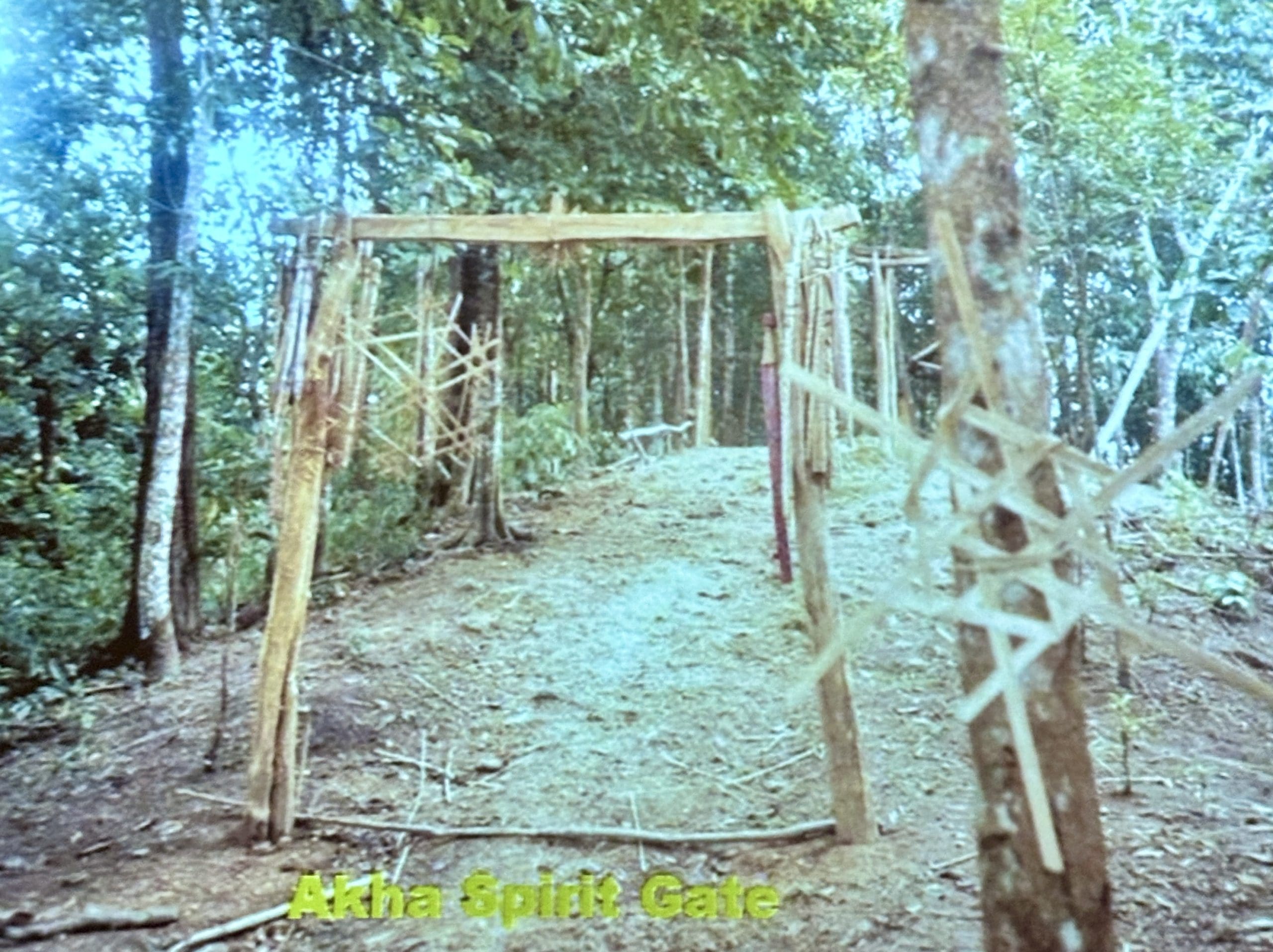

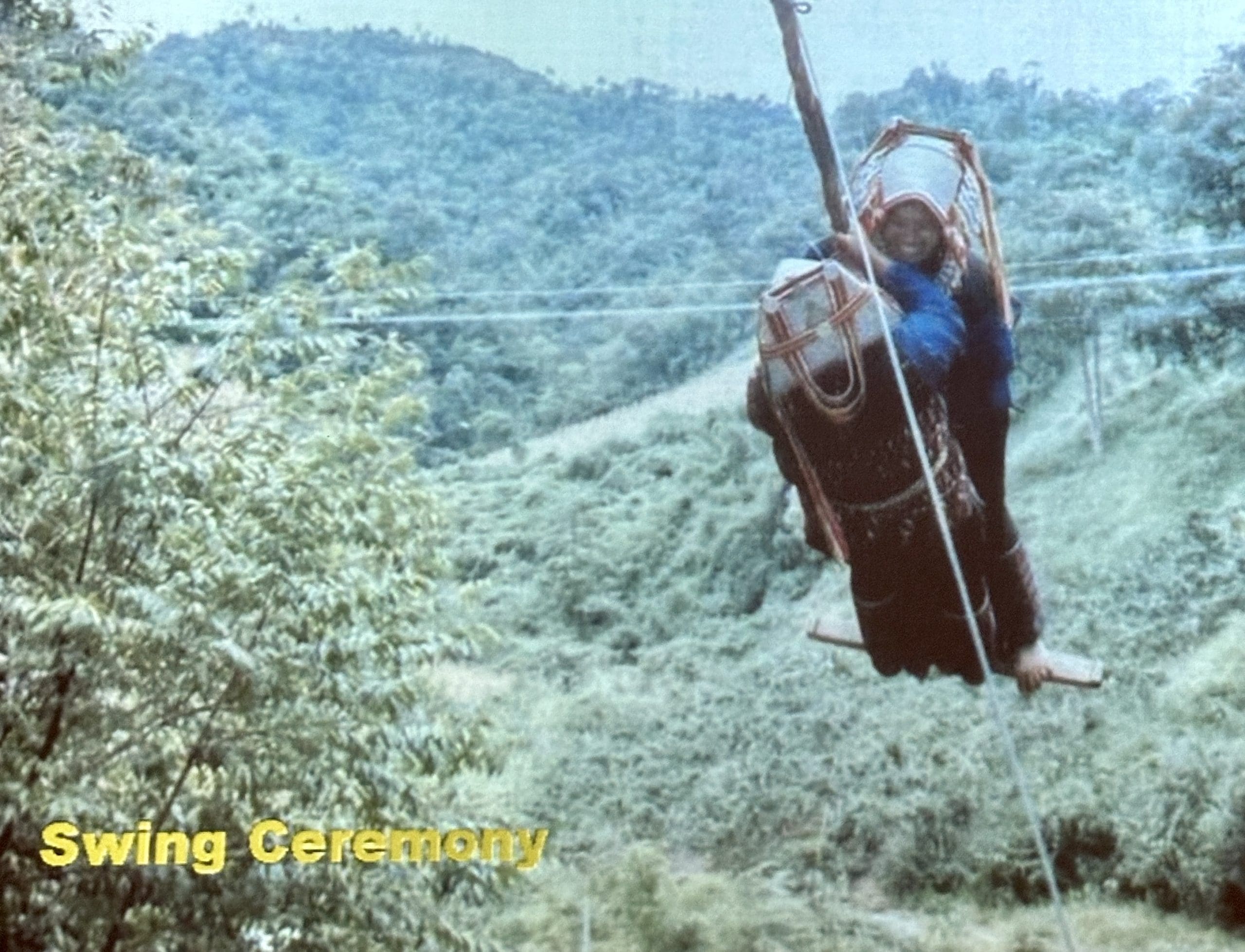

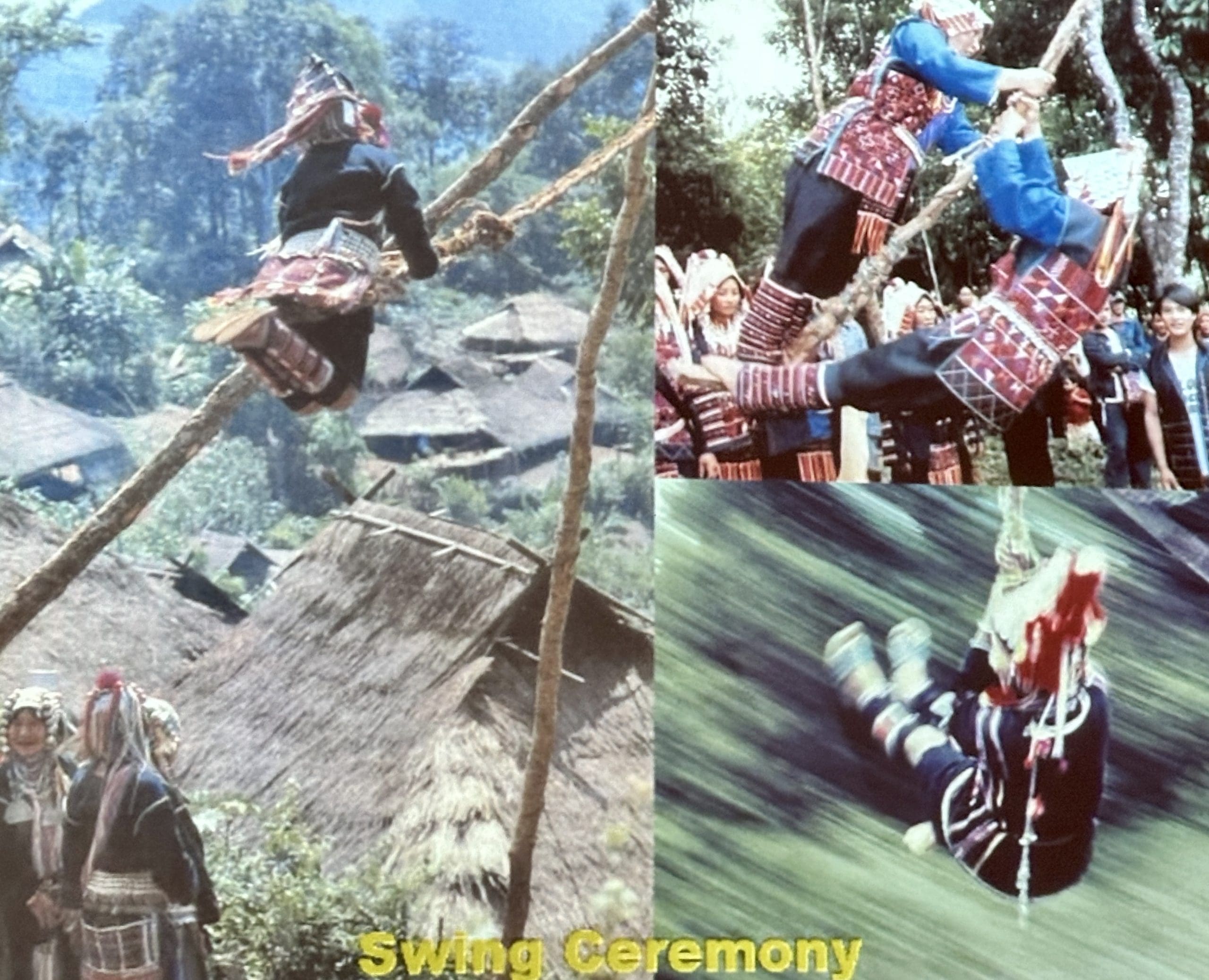

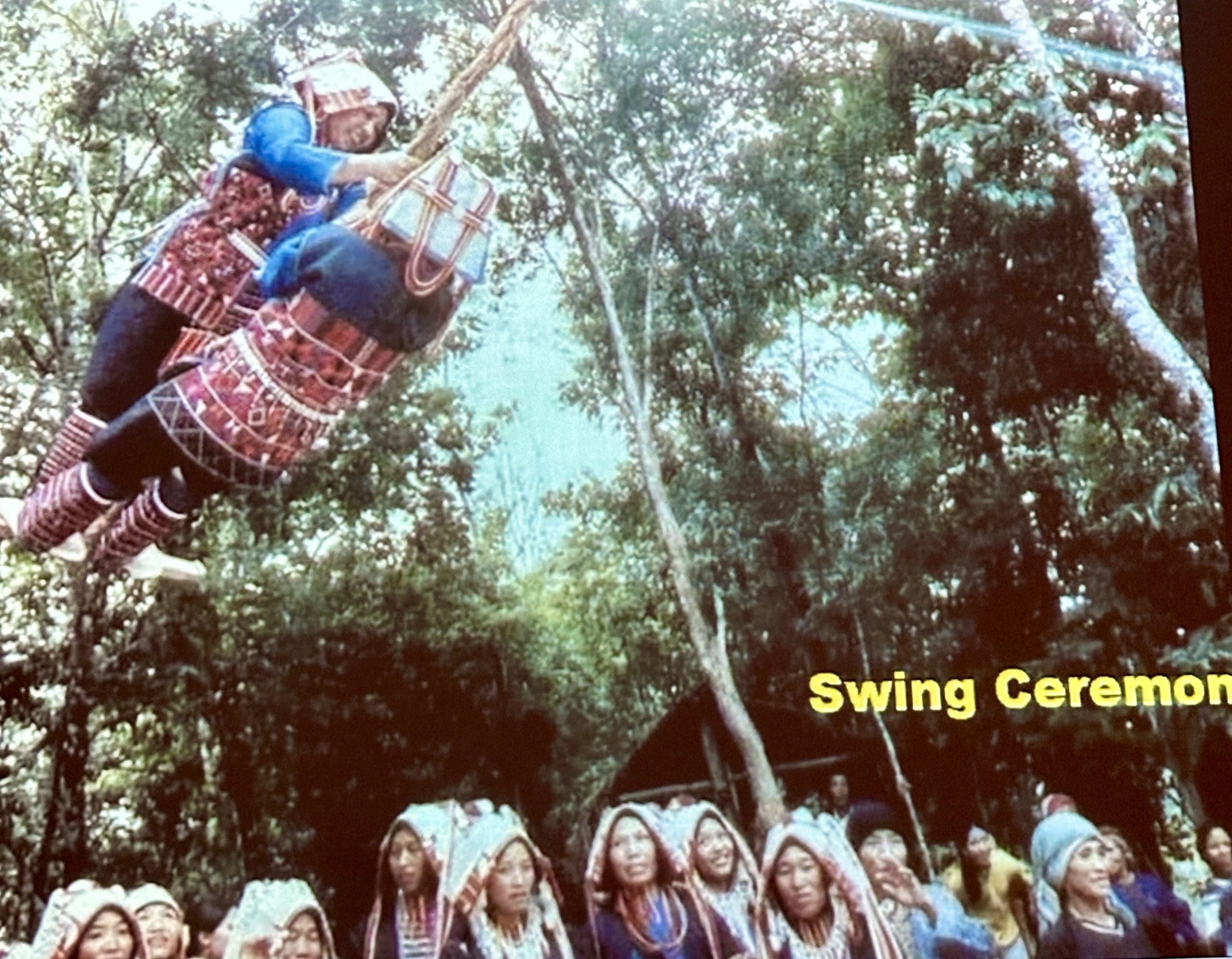

On my night in the Akha village Lahu/Akha village, I saw vestiges of the spirit gates and ceremonial swings shown in the museum photographs below.

Entrances to all Akha villages are fitted with a wooden gate adorned with elaborate carvings on both sides depicting imagery of men and women. It is known as a “spirit gate”. It marks the division between the inside of the village, the domain of man and domesticated animals, and the outside, the realm of spirits and wildlife.

Perhaps the most important festival of the year is commonly known as the Swing Festival. The four-day Akha Swing Festival comes in late-August each year and falls on the 120th day after the village has planted its rice. The Akha call the Swing Festival, Yehkuja, which translates as “eating bitter rice”, a phrase which references the previous year’s dwindling rice supply incorporates the hope that monsoons will soon water the new crop. Festival activities include ritual offerings to family ancestral spirits at the ancestral altar in a corner of the women’s side of the house. Offerings consist of bits of cooked food, water, and rice whiskey. The swing festival is particularly important for Akha women, who will display the clothing they spent all year making and who will show, through ornamentation, that they are becoming older and of marriageable age.

Akha people. (2023, December 27). In Wikipedia

Both the Akha and Lahu people are animists. Many times each day, my guide and the local farmers made offerings to the spirits when we climbed mountains, crossed rivers, found shelter from the rain, harvested food, slaughtered animals, and cooked our food. They did it without self-consciousness or fanfare – it was quite touching.

The Hmong in the “Secret War,” and UXO in Laos and Vietnam

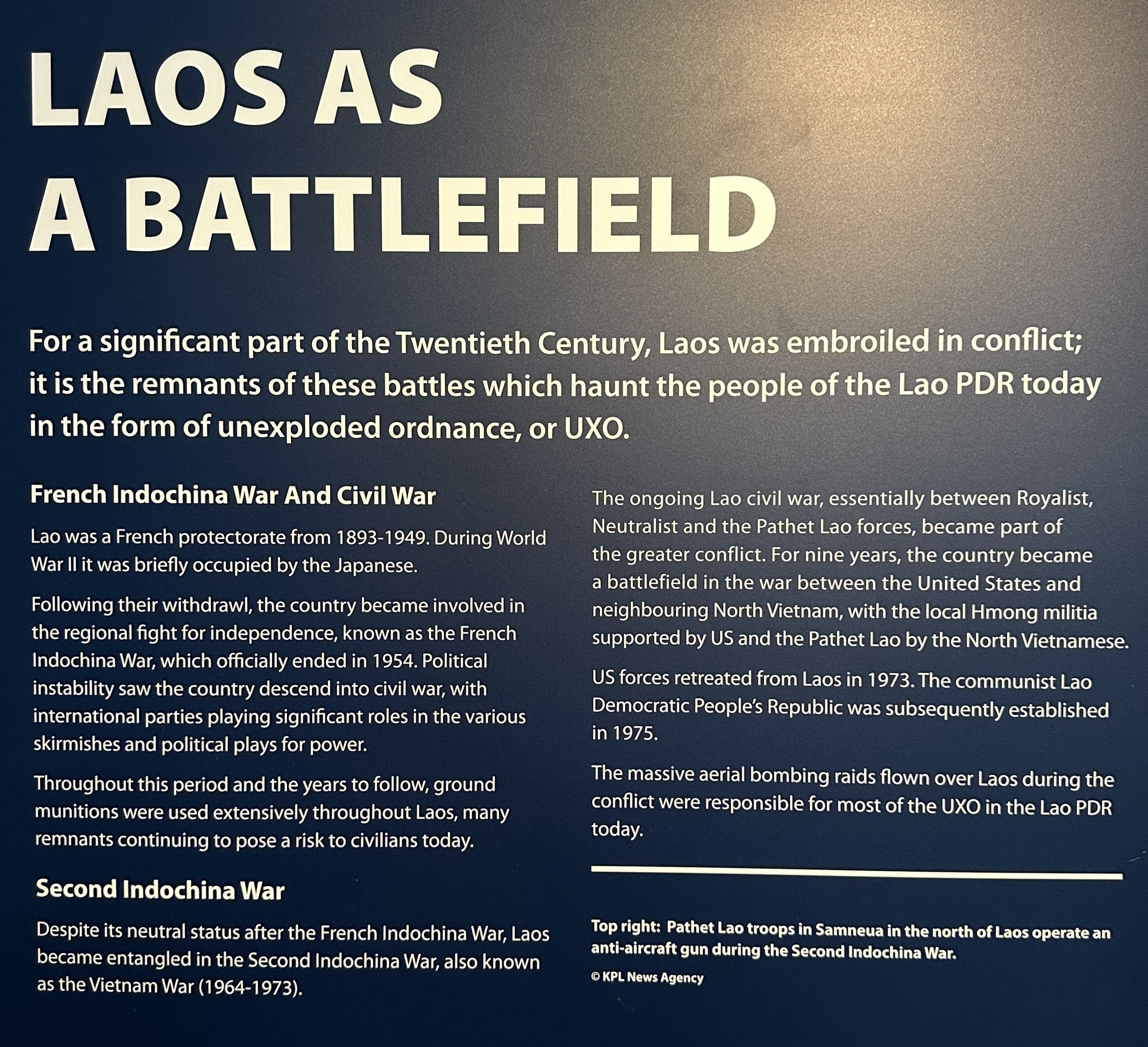

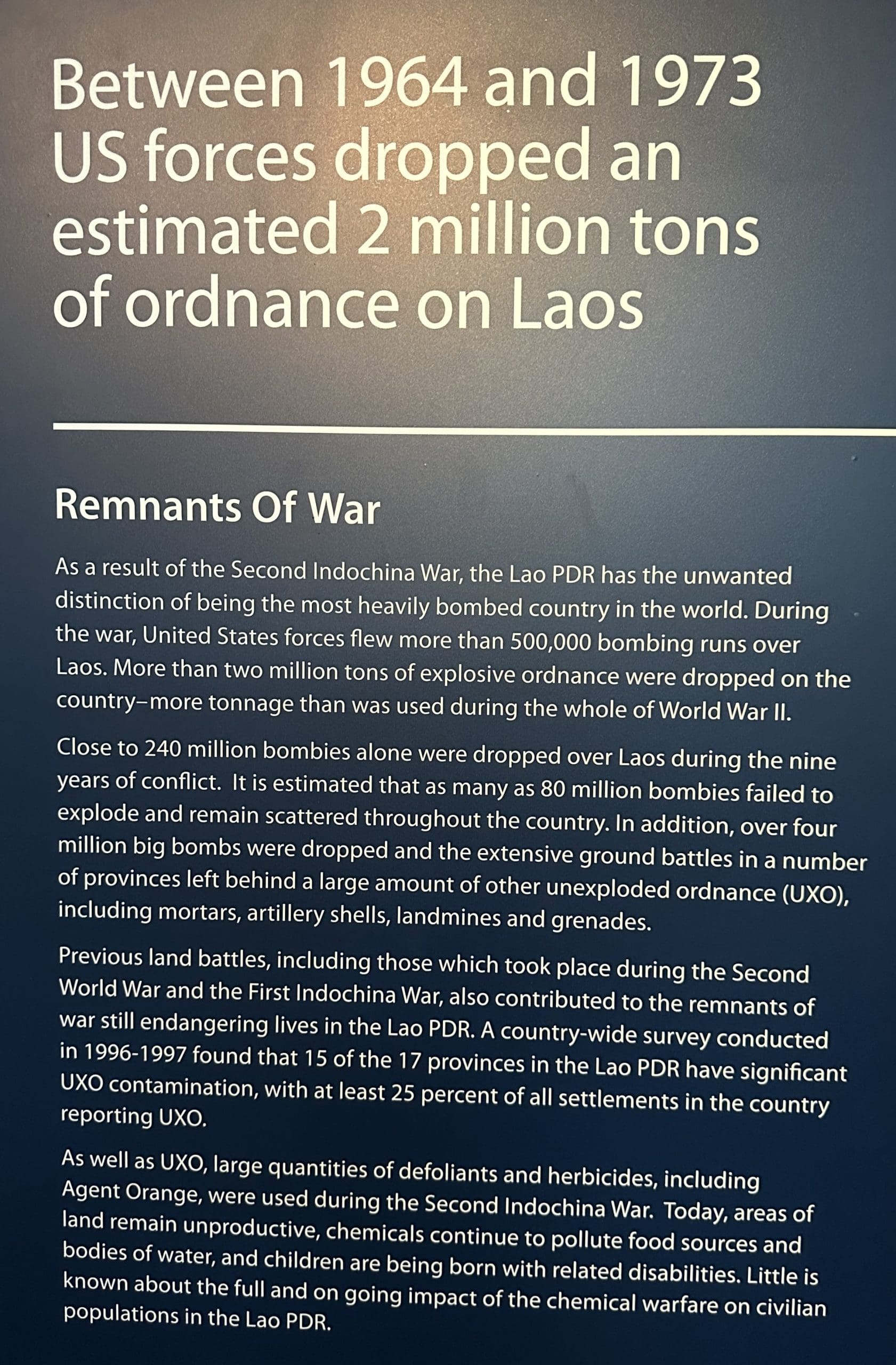

The Hmong became critical allies to both the French and American forces during the Indochina wars following WWII. They were on the front line of defense in the domino theory – intended to stem the spread of communism from China from 1945 to the mid-1970s. This was at the same time that Laos was becoming the most bombed nation on earth per capita – a distinction no country should ever have to hold.

Most of the bombing came from the Americans’ attempts to weaken the Pathet Lao (communist forces in Laos during its civil war) and to destroy the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos used by the North Vietnamese Army to supply the Viet Cong in South Vietnam.

The public didn’t learn about this “secret war” until the 1990s, when classified American files were unsealed through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, and relations between the US and Vietnam were normalized. I learned most of what I know from reading two excellent books:

- A Great Place to Have a War: America in Laos and the Birth of a Military CIA by Joshua Kurlantzick, 2017

- Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942-1992 by Jane Hamilton-Merritt, 1999

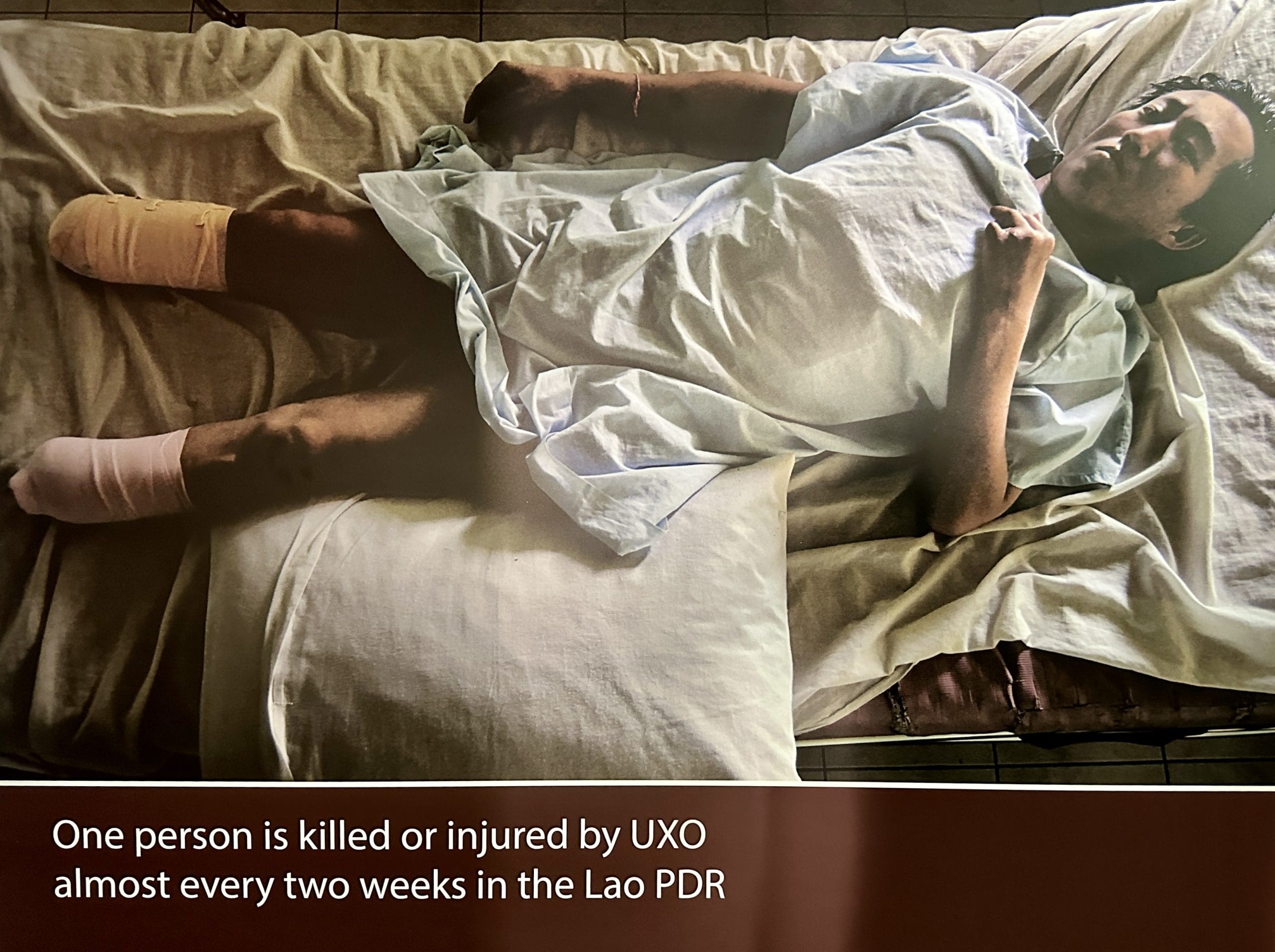

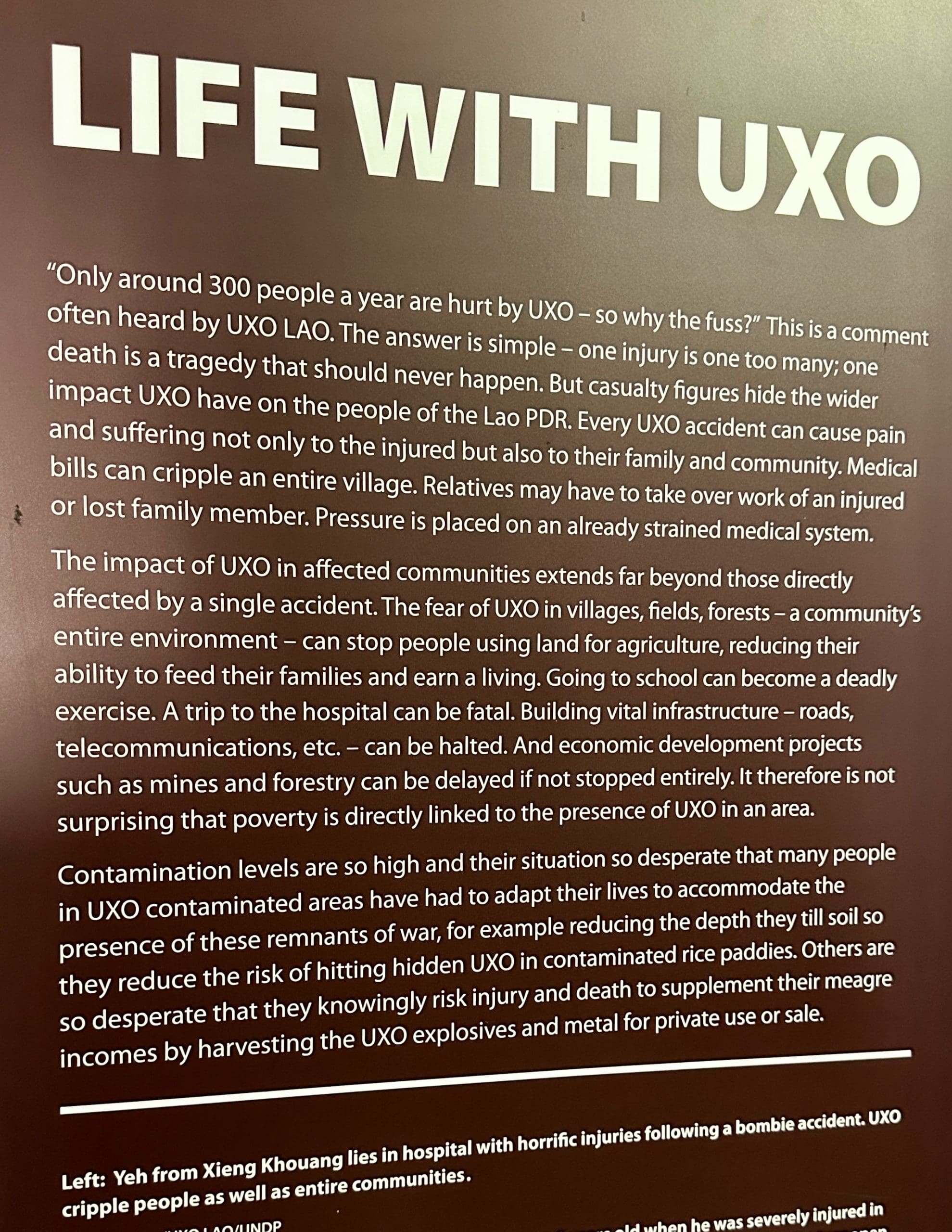

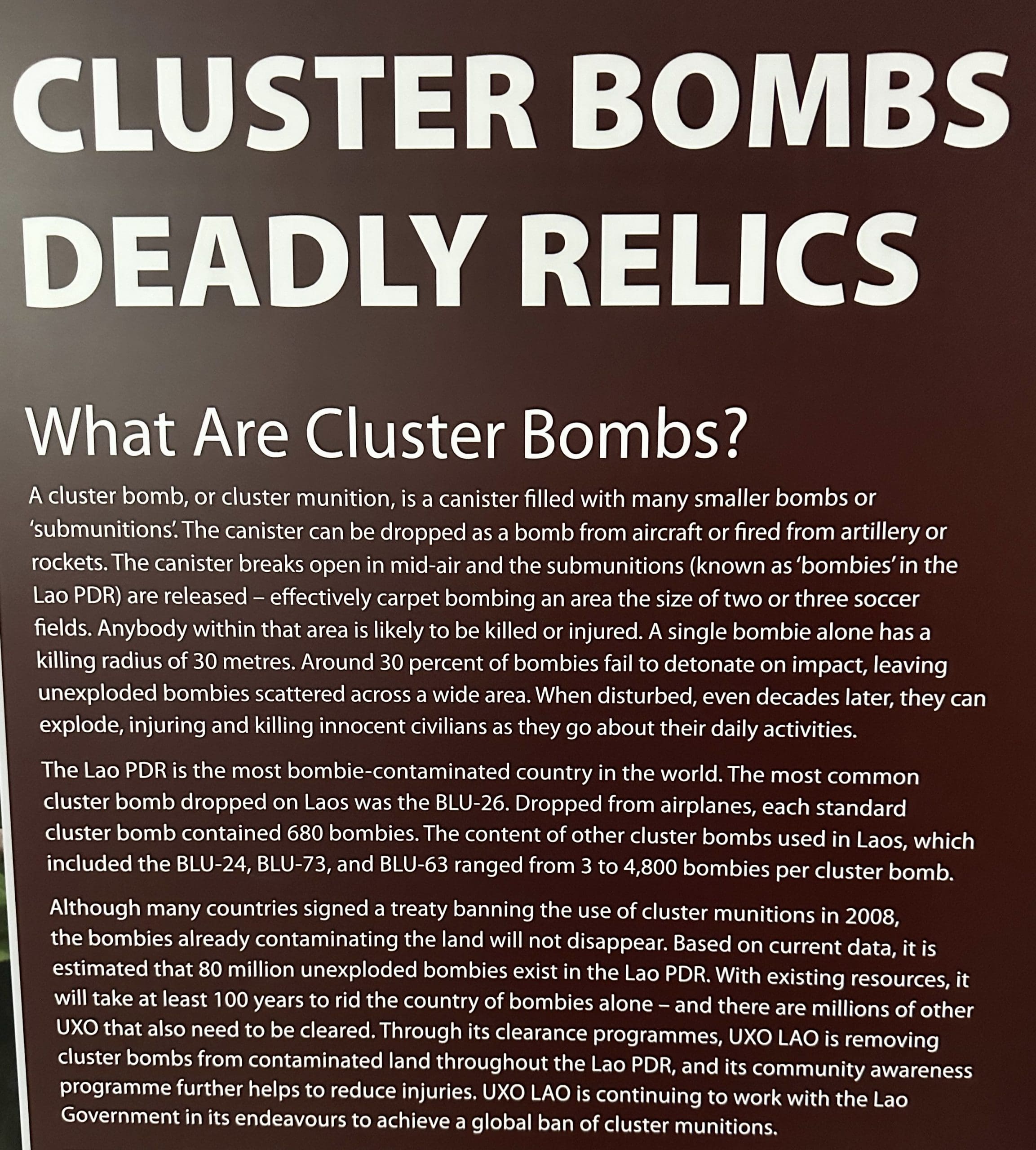

More than two million tons of bombs were dropped on Laos between 1964 and 1973. An estimated 30 per cent of them did not detonate, and continue to kill and injure. They also prevent communities from growing enough food and accessing schools, hospitals and clean water.

MAG UXO Visitor Information Centre, Vientiane, Laos

For much longer than we’ve known about the bombing of Laos, a valiant effort has been made by the Lao National Unexploded Ordnance Programme to clear this beautiful land of the lethal unexploded ordnance (UXO) left behind and educate the public about the risks that still exist. To this day, Loatians are maimed and killed far too frequently: farmers working in their fields, entrepreneurs hunting for scrap metal, and children playing with bright, shiny bombies.

Tragedies never end when the hostilities stop.

What an “eye opener”! So much “out there”! So much about which we’ll never know!

Questions: Are there many tourists that visit that area? And, what was the attitude of the people towards you? (i.e Your features, clothes, language, etc.) (Can imagine a staring contest when first meeting….likenesses, differences, etc.!)

Thanks for sharing your travels – experiences, histories, challenges, …!) Quite an “eye-opening” experience!

Hi, Sue, and thanks for these great questions!

There are several places in SE Asia that are popular with tourists, including the cities of Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Luang Prabang, Vang Vieng, Ha Giang, and Hoi An from which I started some of my side trips. Those city residents are accustomed to visitors from the West, China, Korea, South Asia, the Middle East, and more recently from Ukraine and Russia. Villagers, even a few miles away, get much less exposure, but everyone seems to have at least some internet access so they’ve heard foreign languages and seen “us” on Facebook or TikTok.

Outside of the traditional ceremonies, almost everyone’s daily attire is functional (trousers, shorts, t-shirts, hoodies, and caps). The only time I got “stares” of curiosity (or fright) were with little kids in remote villages. Attitudes ranged from civil welcoming to complete indifference. For an example of the latter, when I was invited to join family members or friends for a meal, they focused on their own conversations and ignored me. They politely answered my questions, but had few questions for me in return, so I was most often just a fly on the wall: observing, but not partaking. This was in sharp contrast to the very warm welcomes and “20 questions” I often experienced with new people in Namibian towns and villages.

I was particularly interested to see the rural Lao and Vietnamese people’s behavior towards me as an American, given the tragic history our countries shared. Those of an age that lived through that traumatic time had absolutely NO interest in speaking about it. The younger people couldn’t care less – they were either struggling with their own life challenges or were too engaged with the dynamic energy of their busy lives.

Fascinating Chris. Mahalo.

Never heard of the Secret War.

Did you try the swing?

Aloha.

Haha! No, I saw a couple but the swings operate only during the ceremonies.